The Space between Innocence and Experience

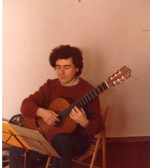

An Interview with the classical guitarist and composer Ganesh Del Vescovo

by Baret Magarian

There's something about the story of Ganesh Del Vescovo's life which comes from the realms of fiction. One could imagine a novelist inventing that life in a narrative which stresses serendipity, vast cultural contrasts and mystical experience. For these are the ingredients of that life. Over the course of several meetings with Del Vescovo I was given a glimpse into the nature of his almost monastic devotion to his art. As a classical guitarist, he has not only mastered his instrument but invented new techniques and even new instruments. As a composer his body of guitar music is notable for its limpid resonance, often creating a feeling of sublime detachment in the listener.

He is now based in Florence though he spent his formative years in an isolated area of the Abruzzo, a region of Italy that was, as he was growing up, the essence of the rustic and rural. There was, as he puts it, nothing there apart from the embrace of magnificent and stark landscapes. "No shops, no TV, no newspapers." He spent his formative years locked in this rural bubble, having no idea of the outside world or of outside culture. At school he played truant, preferring to ramble through the countryside like some Fellinian aberrant. At this time he seems to have developed a dexterity with all things manual, driving a car without a license, working in the fields, learning that his hands were his greatest asset. Then at the age of sixteen he transferred to Rome to live with his aunt, where he chanced upon a guitar with only one string. Something like a revelation took place.

He is now based in Florence though he spent his formative years in an isolated area of the Abruzzo, a region of Italy that was, as he was growing up, the essence of the rustic and rural. There was, as he puts it, nothing there apart from the embrace of magnificent and stark landscapes. "No shops, no TV, no newspapers." He spent his formative years locked in this rural bubble, having no idea of the outside world or of outside culture. At school he played truant, preferring to ramble through the countryside like some Fellinian aberrant. At this time he seems to have developed a dexterity with all things manual, driving a car without a license, working in the fields, learning that his hands were his greatest asset. Then at the age of sixteen he transferred to Rome to live with his aunt, where he chanced upon a guitar with only one string. Something like a revelation took place.

"I started playing this one string one night. I had a sense of something in myself emerging, something profound and magnetic. It was as though I was brought into another dimension. It was not an emotion as such but a sense of spirituality which led to the birth of a new point of view of the world. I wanted to re-create this feeling and this led to my desire to become a musician." Subsequently he purchased the other strings, tuning the guitar according to his own scale and inventing, even at the outset, his own techniques, specifically the pizzicato Ganesh. In the meantime in Rome he took various jobs as a dish washer, chef's assistant, waiter, and upholsterer. When he was 19 he returned to the Abruzzo.

One of the most striking things about our conversation was the insight he gave me into his method of composition. Unlike many artists his environment plays absolutely no part in his ability to create. Whether he is in the city or countryside, whether the setting is tranquil or noisy makes no difference, (for example the piece "Jasidhih Express" was written on an Indian train full of families with children, travelling between Kolkata and Delhi). Because he is so centred and focused inside himself the externals of the outside world and what is going on there don't come into the creative equation. The music just arrives and when he doesn't have the impulse to compose he doesn't force himself. In this regard his methodology recalls the idea of the Aeolian harp, which was "played" by the wind or that state of conscious intoxication which led to the creation of Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem Kubla Khan. But it should be stressed that his interior world is also linked to his practice of meditation and abiding love of Indian spirituality and yoga. It's also worth pointing out that he had never even heard any music of a classical nature. In keeping with his striking level of naivety and innocence he assumed everyone has the ability to just play and compose music. If ever there is a story of a contemporary prodigy just picking up an instrument and mastering it without formal instruction Del Vescovo is a prime candidate.

He came into contact with a distinguished Florentine teacher, Alvaro Company, who was so flabbergasted by his talent that he offered him free lessons, and Del Vescovo acquired an academic grounding that he had hitherto lacked.

He came into contact with a distinguished Florentine teacher, Alvaro Company, who was so flabbergasted by his talent that he offered him free lessons, and Del Vescovo acquired an academic grounding that he had hitherto lacked.

Now, in around 1982, he was living the life of an emaciated gypsy in a caravan, surviving on the equivalent of 25 euros a month, based in Florence. He had various encounters with the law, most of which centred round the illegal parking of his caravan. He and his mobile home ended up at one point in Piazzale Michelangelo, whose fountain offered Del Vescovo a source of running water. But the officers who first targeted him ended up bending the rules and granting him favours, somehow won round by his all pervading ignorance of how society functioned. He seems at that point like some figure out of Rabelais, the archetypal and inventive misfit surviving on his wits. Then he began to study at the conservatory. Despite the severity of this experience (at least ten hour days of rehearsal and practice) he managed to keep his spontaneity intact. This spontaneity goes hand in hand with his experience of time, which he doesn't register in a conventional fashion. "I don't recall years, dates. I have no real sense of linear time passing. Now I feel younger at the age of 49 than I did at the age of 20 because my viewpoint is wider, my sensibility is greater. I feel more alive to nuances, tones and textures. At the same time I realise that music can give me some happiness but it is ultimately ephemeral. Artists can never be happy. If I was I wouldn't be composing. Music forms a bridge to the other, spiritual world, which is a world of timelessness."

It is instructive to think of this world-view forming and taking shape in such humble, impecunious circumstances as those in which he found himself. Or perhaps precisely for that reason. Del Vescovo's art is his life, so he has no need of the exterior accoutrements, pleasures, drugs that we surround ourselves with. But the caravan was eventually substituted by an ashram, when he was introduced to Uttarkashi Biswas, a Swami who was teaching yoga with her husband Anusandhana. An instant rapport was established between the family and Del Vescovo, and he moved in with them. His period of wandering was at an end and his career started to flourish, as he gave recitals in Tuscany, in Italy, India, Japan and Europe. He has recently also embarked on an intensive study of the tabla and the sarod, mastering both very quickly.

It is instructive to think of this world-view forming and taking shape in such humble, impecunious circumstances as those in which he found himself. Or perhaps precisely for that reason. Del Vescovo's art is his life, so he has no need of the exterior accoutrements, pleasures, drugs that we surround ourselves with. But the caravan was eventually substituted by an ashram, when he was introduced to Uttarkashi Biswas, a Swami who was teaching yoga with her husband Anusandhana. An instant rapport was established between the family and Del Vescovo, and he moved in with them. His period of wandering was at an end and his career started to flourish, as he gave recitals in Tuscany, in Italy, India, Japan and Europe. He has recently also embarked on an intensive study of the tabla and the sarod, mastering both very quickly.

A DVD is due to be released shortly and his website features his compositions and essays about his musical style and innovations. It is a remarkable story, which fuses so many ideas about what is the best way to live and what the meaning of art really is. We end our conversation on a tantalizing note. He looks distracted and then energised. "We all have this talent inside us. It's a question of pulling it out, mining down to it, finding it. The material inside us is the same, but its expression changes depending on the individual." In terms of mining I feel he has gone down further than most. Luckily for us he has also returned.

Florence, November 2008

The author, Baret Magarian, is an English writer who has collaborated with many English newspapers and reviews. At the moment he is living and working in Florence and is preparing a novel set in Florence and Lisbon.

Italian

Italian English

English